Poems of Friedrich Hölderlin

Translator's Blog — Page Two

Does Hölderlin qualify as Weltliteratur?

Nationalliteratur will jetzt nicht viel sagen, die Epoche der Weltliteratur ist an der Zeit, und jeder muß jetzt dazu wirken, diese Epoche zu beschleunigen. (…) Im Bedürfnis von etwas Musterhaftem müssen wir immer zu den alten Griechen zurückgehen, in deren Werken stets der schöne Mensch dargestellt ist. (Eckermann, Gespräche mit Goethe, 31. Januar 1827)

National literature no longer means much: the time for world literature has come, and everyone should act to hasten the new era. (…) To satisfy our need for models we must always return to the ancient Greeks, in whose works the ideal human being* is represented. (Eckermann, Conversations with Eckermann, 1827)

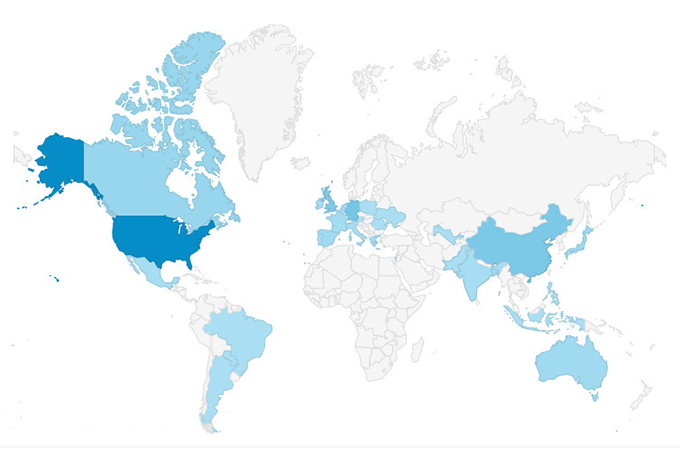

Google Analytics map for this website as of October 20, 2020.

Goethe's humanitarian vision for a Weltliteratur of the future, based on the ideals of ancient Greece in order to determine what qualifies as authentic literature to begin with, seems congenial with Hölderlin's own attempts at establishing interactions between Greek culture and the German poetry of his day. Yet Goethe's thoughts about the term he is credited with inventing were more or less ongoing, and public debates since then have transported it to ever higher levels of complexity.

Objections arose to limiting Weltliteratur to the standards enjoyed by Western national literatures as covert colonialism, in which alien counterparts were viewed as possibly interesting, but too exotic or parochial for integration. Questions then appeared whether international success should constitute a proper category of normative aesthetics, and it has also been suggested that the graduate study of Comparative Literature which developed in the U.S. after WWII might be better organized as a comprehensive study of world literature. More practically-minded analysts have elaborated upon Goethe's project by observing the progress of book translating, international book commerce and burgeoning global Internet operations.

Realistically, Hölderlin remains pretty much unknown outside Germany. More often he functions as an unexpected discovery for German language students interested in literature, who are equipped with sufficient skills to digest stylistic peculiarities of the Romantic era as well as the poet's own idiosyncrasies. As far as I know, no publisher has made plans to publish Hölderlin's collected works in English or French translation, which seems a relevant criterion for Weltliteratur status. And I fear that if his writing is ever to rise to the kind of global inspiration and effectuality imagined by Goethe, he is likely to do so mainly in English, which necessitates very skilled translation work.

Just as a footnote to these ruminations: Google Analytics confirms that in the past 90 days, roughly half the users of this website have come from the United States and Germany, while the remainder have arrived from Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Paraguay, Mexico, Spain, Italy, Portugal, U.K., Ireland, Greece, Poland, Romania, Ukraine, India, Pakistan, Romania, Phillipines, St. Lucia, Uzbekistan. According to the map provided by Google and appended above, that's quite a chunk of world.

* “Der schöne Mensch” signifies the fusion of ethics and aesthetics, a perception which fuelled European admiration for Greek arts and literature from the middle of the 18th century. “Ode on a Grecian Urn” by Keats is a lofty example.

— 10/21/20

Blog Page One

Blog Page Two

Blog Page Three

Blog Page Four

Blog Page Five Home Page

Website and Translations Copyright © 2022 by James Mitchell