Poems of Friedrich Hölderlin

Translator's Blog — Page One

Why you must not read these translations!

Werner Herzog, in The Mandalorian, Disney+ streaming service, 2019.

Werner Herzog, in The Mandalorian, Disney+ streaming service, 2019.

"Hölderlin, the greatest of the German poets. You cannot touch him in translation. If you’re reading Hölderlin, you must learn German first.” — Werner Herzog, interviewed in The Guardian, 19 June 2020.

I won't argue that reading my translations is better than reading the German originals, but following Werner Herzog's position one might conclude there's no point in reading Shakespeare unless in English—never mind that Elizabethan usage is frequently unintelligible to the native English reader without footnotes. So if you're German, better not put aside those wonderful Schlegel translations of Shakespeare, which practically converted him into a national poet of Germany.

Unlike many other poets of his times, Hölderlin has interesting and perhaps even important things to say, and there's no need, in the interest of linguistic aesthetics, not to share the wealth with those unfortunates handicapped with an ignorance of the German language.

— 6/21/20

Was Hölderlin a Romantic?

Some critics cannot resist classifying Hölderlin as a Romantic poet, mainly I suppose because he lived in that era and shared the same poetic vocabulary. In fact he had not much in common with his contemporaries, who binged with delight on Volkslieder, ballads, German antiquarianism, traditional rhymed verse forms, as well as yearning for the Infinite and so forth. Perhaps Hölderlin's reluctance to participate might have contributed to the indifferent reception of his published poetry, although you can find themes one could certainly label "Romantic" in the Hyperion novel and Death of Empedocles play.

Hölderlin adapts and transports ancient Greek literary and religious tradition into German poetry, which in his last and best creative phase resulted in the unrhymed, discursive, celebratory, hymnic writing which he received from Klopstock and Pindar and then carefully adapted into his writing. Although similar impulses date back a half-century earlier in both Germany and England, his is a unique accomplishment which doesn't happen elsewhere as convincingly or enduringly, and it is also what separates him from, not unites him with, the Romantic movement. Indeed you might understand some of the Late Hymns—such as Mnemosyne and The Ister here translated— as breakthrough poems into postmodernity.

— 6/25/20

“I love the smell of book ink in the morning.” – Umberto Eco

An expanded third-edition of all the translations on this website was published on July 1, 2020 and is available at

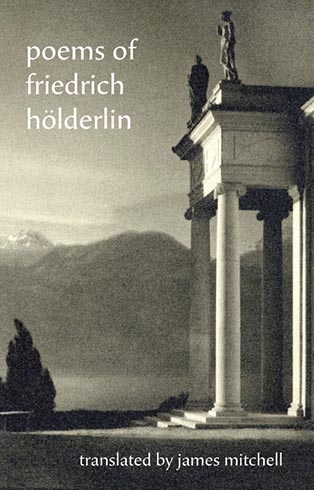

spdbooks.org, and soon at amazon.com. I confess I was getting a bit tired of the "Old Germany" imagery one is assaulted with when reading about the poet, so I sprang for a 1930s German futurist photo by Erich Angenendt on the cover. If you'll forgive the somewhat heavy-handed symbolism, the idea is that it's a Greek temple (in reality an Italian copy of a Roman one) and in the distance are the Alps, pointing the reader towards Deutschland, which is much of what this poet is about.

—7/1/20

Alma mater dolorosa

Tübinger Stift in 2009. Thx Flickruser Joachim Hofmann.

I came across an interesting quote from a letter H. wrote to his new friend GWF Hegel on October 24, 1796 concerning the college (Tübinger Stift) where both studied:

"Das Stipendium riecht durch ganz Württemberg und die Pfalz herunter mich an wie eine Bahre, worin schon allerlei Gewürm sich regt." (StA Br.127).

"The college smells throughout Württemberg up to the Pfalz (i.e., as far as Frankfurt) to me as if it were a hospital stretcher, on which all kinds of worms are moving around."

Maybe an example of teenage sociopathy, but the critical mindset of the two friends is already apparent at age sixteen.

—7/7/20

Blog Page Two

Blog Page Three

Blog Page Four

Blog Page Five Return to Home Page

Website and Translations Copyright © 2022 by James Mitchell